Vurdering av hvor mye tilfeldigheter påvirker rettferdige tester

Tilfeldigheter kan få oss til å begå to typer feil når vi skal fortolke resultatene av rettferdige behandlingssammenlikninger: vi kan konkludere med at det foreligger forskjeller i behandlingsutfallet som faktisk ikke eksisterer, eller også kan vi tro at det ikke er forskjeller selv om de virkelig finnes. Jo flere observasjoner vi gjør, desto mindre er sannsynligheten for å bli villedet av tilfeldigheter.

Sammenlikninger kan ikke gjøres for alle som har fått eller kommer til å få behandling for en aktuell tilstand. Det vil derfor aldri være mulig å finne den ”sanne forskjellen” mellom behandlingsmetoder. Studier gir i stedet velkvalifiserte gjetninger om hva de sanne forskjellene er.

Påliteligheten i estimerte forskjeller angis ofte ved bruk av ”konfidensintervall” (confidence interval = CI). Det er overveiende sannsynlig at den sanne forskjellen befinner seg innenfor det angitte konfidensintervallet. De fleste mennesker er allerede kjent med hva et konfidensintervall er, selv om ordet i seg selv kan være ukjent.

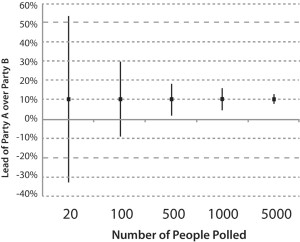

The 95% Confidence Interval (CI) for the difference between Party A and Party B narrows as the number of people polled increases (click to enlarge).

For eksempel kan en meningsmåling i forkant av et politisk valg rapportere at parti A ligger 10 prosentpoeng foran parti B, men rapporten vil da ofte opplyse om at forskjellen mellom partiene kan være så liten som 5 poeng eller så stor som 15 poeng. Dette “konfidensintervallet” angir at den reelle forskjellen mellom partiene sannsynligvis befinner seg et sted mellom 5 og 15 prosentpoeng.

Jo flere mennesker som deltar i meningsmålingen, desto mindre usikkerhet knytter det seg til resultatet, og konfidensintervallet blir følgelig smalere.

Akkurat som man kan fastsette graden av usikkerhet rundt en estimert forskjell i andelen velgere som støtter to politiske partier, kan man også fastsette graden av usikkerhet knyttet til en estimert forskjell i andelen pasienter som blir bedre eller dårligere etter to typer medisinsk behandling. Her gjelder det samme: Jo flere pasienter man sammenlikner – la oss si antall som blir friske etter et hjerteinfarkt – desto smalere blir konfidensintervallet som omgir estimatet for behandlingsforskjellen. Dess smalere konfidensintervall, desto bedre.

Et konfidensintervall følges gjerne av en indikasjon på hvor sikre vi kan være på at den sanne verdien ligger innenfor det angitte området. Et 95 % konfidensintervall betyr for eksempel at vi kan være 95 % sikre på at den sanne verdien av det som estimeres ligger innenfor konfidensintervallets bredde. Det betyr at det er 5 % (5 av 100) sjanse for at den sanne verdien ligger utenfor intervallet.

-

Steve George

-

Anonymous

-

Paul Glasziou

-

-

Robert42